2023 – Volumi – GALLERIA GABURRO – Milan

The sound of painting

- Rhymes, rhythms

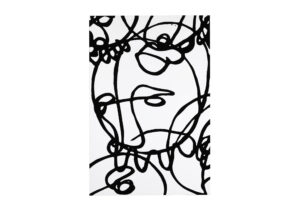

Danilo Bucchi’s work, the immediacy of which makes it appear simple, nonetheless presents complex conceptual problems. First and foremost, there’s a challenging question: how can we convey painting beyond the rigorous models of that which is visible and, at the same time, tether it to the perception of its volume in terms of its tactile, almost sculptural dimension, as well as to our reminiscences of music and rhythm, so that we might unearth its musical aspect?

Indeed, for his multiple expressions — installation, photography, painting or even in works of a digital nature — the artist always reverts to a process that we can define as being rhythmic in nature, which allows us to perceive his intense relationship with musical notation. That is the way in which every gesture, every sign, every movement of the body – because we what we’re really talking about are the body’s gauges – which is projected onto the surfaces and which we find continuously in his work, is highlighted as a form of gesturing similar to improvisation, to musical notation and even to concrete poetry. This, together with the ability to move towards John Cage’s games of chance, reveals a major performative indicator: as Achille Bonito Oliva said in this regard, “Beyond, there are the unexpected aspects of life and forms in his creativity”.

Hence, what we immediately perceive upon first coming into contact with his work invariably refers us to a perceptive sense which, through our body, we understand also originates from the movement of another body, almost functioning as if it were in a performative dimension. Indeed, the artist’s work, his elegant and subtle gestures, which we almost view as being like a style of writing – which, on an erudite level, is reminiscent of Cy Twombly, as well as of Henri Michaux, and which also dialogues, on another level, with the graffiti that floods the streets of our cities — presupposes, in its execution, the performative movement of the body and the strong inscription of gesturing in the painting, which tends to immediately ascribe it to the occurrence.

That’s because, in reality, however discreet and almost capricious this gesturing may seem to us, with its structuring of spaces whose nature is, so to speak, baroque, implies an association with the space of painting that requires the body to perform its own gestures, in improvisation, capable of an inscription movement which, as Bonito Oliva had so profoundly understood, transports it to a dimension which is, above all, vital. It also determines, in its communication, an almost invisible, yet sensitive presence of a structure of rhythms and rhymes that continuously lead the forms of the drawing out of themselves, generating an ambiguous space, since it is populated by a kind of feverish calligraphy.

The practice of a poetic order that in reality draws his work, albeit distantly, closer to the great tradition of automatism which, from Mirò to Pollock and from Henri Michaux to Jean Dubuffet and later to Alechinski, defined a new form of relationship between images and signs, between painting and writing, a powerful relationship based on the notion of rhythm that the 20th century continuously reintegrated, understanding the need to revert to the archaic source, or even the hieroglyphic point of reference.

- The Egyptian moment

It was the Italian philosopher Mario Perniola who began insisting on the possibility of an effect and also of an Egyptian moment in art and society, to try and explain some of the typical signs of contemporaneity by noting, through this designation, the simultaneous presence of multiple temporalities cohabiting in the present time, which the philosopher also considered a characteristic of archaic Egyptian culture: “If everything can be moved back, nothing is current, and likewise everything is repertoire, because everything can immediately become the present[1]”.

Hence, we can say that Bucchi’s work inscribes part of the order of an Egyptian moment, since presences mysteriously converge within it that not only connect it to its own time – particularly in the ways in which it assumes the relationship with photography, languages of installation and even the intensities of the digital expression —, but also dialogue with numerous other visual sources.

That is how his works subtly link to countless artists of various centuries before ours, the current one: as mentioned above, from Baroque art to the 20th century, there are many connections since his work has unexpected relationships with Pollock, Saura, Michaux, Dubuffet and even with current urban graffiti.

However, why mention Baroque here? If we pay a little attention to its internal method of construction, we can immediately see that Bucchi’s work continuously inscribes these variations, almost like watermarks, in which the line develops as if it were dancing in the entire space at its disposal. If, according to Wolfflin, the line was more a typical sign of classicism than of Baroque, being the result of the mark, the fact is that in these numerous lines moving incessantly in his work, in a gesturing that hesitates between the figure and the purest abstraction, the artist makes the suggestion of the mark appear, from the nervous impulse of this movement. Not so much because he seeks the mark, but because it makes itself appear, albeit continuously hesitant among the blacks and whites.

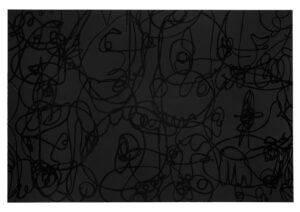

Baroque is, therefore, this nervous, urgent shimmering that the hand intensely applies on the surface, as if seeking saturation, like the almost sculptural aspect that it unleashes gradually, vibrating in the multiple spaces it generates and which, like Leibniz’s folds, transports us into a universe of artificial sensitivity. In the same way in which colour acquires its thickness, it suggests the possibility of a sculptural unconsciousness that runs through all of his painting from within, as if it were all tied together, through these diagrams made of Borromean knots (mentioned by Lacan), which underline the unconscious aspect that in reality seems to inhabit it.

- The image of the multitude

At first glance, the fluidity of the lines is structured like a musical score and its notation on the surface of the painting suggests the animated writing of signs apparently destined to be translated into sounds. Immediately afterwards, it suggests the animated presence of figures, numerous figures that would seem originate from some street graffiti in one of our cities, suggestions of a crowd which, as in political manifestos, cause what we identify as the image of the multitude to arise before our eyes. In this sense, this is an intensely urban, contemporary, vibrant, suggestive art form, animated by a subtle hieroglyphic tension that we aren’t immediately able to decode, since it displays an intense, indecipherable and even fractal texture.

Just as happens when looking at Pollock’s drippings, we could say that, when faced with these movements of colour and the gestures that animate them, they correspond to impulses that reverberate thanks to the immediate presence of that same gesture, a body’s intensities of dance. Almost convulsive, as a result of the urgency of a performer who, on a blank canvas — the screen — allows the development of complex plots, impulsive, seismographic movements, of a current reinterpretation of action painting, trying to establish, at this impetuous speed, a kind of automatic movement of sensation.

However, immediately afterwards, and thanks to our habit of seeing and observing, we understand that these micro-gestural forms are also delicate figural suggestions. They evoke the complex texture of the dense figurations of António Saura, the great Spanish artist whose figures come from a night inhabited by the ghosts of dance – of the cante jondo and the flamenco – whose contracted movements return to the scene in figurations with an almost dramatic slant. However, this movement of the line, immediately afterwards, suggests a remote connection with Burri’s interrupting gesture, or with the lines torn on the canvas by Lucio Fontana.

In the Egyptian moment, they actually gather multitudes, truly multitudes of figures originating from multiple, erudite and popular references, which we could view as distant from each other. Nevertheless, they highlight the ability, in the same fluttering of the line, to attract the memories of Clifford Still, as well as the nervous register of the archaic line on walls, which taught us the flowing painting of Cy Twombly.

Indeed, everything in Danilo Bucchi’s work is simultaneously an automatic and impetuous register of an enigmatic “knowledge from the abyss” — that connaissance par les gouffres of which Henri Michaux spoke — an animated form of what we could call the vestige of dancing gestures, unpretentious and with a so-called Nietzschean nature, since it seems to be entirely constructed as the memory of a dance of the spirit itself or, more simply, as a liberating movement of a hand on a wall. The same, therefore, as the other that the young graffiti artist who walks our cities in the night leaves inscribed, as a sign of life or as a trace for all those who pass by the walls that hide the houses.

Street art and erudite art, that of Danilo Bucchi walks between registers which he mysteriously connects and embraces in a singular ability to establish as concrete, impetuous composer registers of life itself: in this sense, his is a poetic art, more than the art of painting, since in many respects it seems to us that the order of poetry precedes the order of image.

- The empire of signs

It is in this intersection that we may find the most exact key to Danilo’s enigmatic plastic universe: between poetry and painting, sculpture and gestures, signs and symbols, his art hints at another field from afar, one that is perhaps less evident: the photographic image, a practice which he also developed.

In a series that he produced, called Japan Diary and which remains unpublished, the artist clarified his processes and we can therefore understand what consists of that which, according to Deleuze, could be designated as his formula, that is, in a synthetic register, precisely diagrammatic, in which the photographic image triggers an idea of the urban space which then re-emerges in his painting as already synthesised. Indeed, in his plastic work, Danilo Bucchi tries to formulate synthetic images capable of conveying intensities, impulses, signals of an almost graphic nature, of what is the writing of life in the cities, which he captures in the style of the Baudelairean flanêur.

The vision of the city appears synthesised or, rather, diagrammed, as if commencing from the condition of being only a blank sheet on which a variety of multiple, closed signs could be inscribed: everything seems organised in the streets, squares, public spaces, whether they be buildings or walls, avenues or gardens, as if obeying the same impulsive logic born of the very movement of life, writing themselves onto the urban space.

His pictorial references, which I mentioned above, serve not so much as a way for him to incorporate erudite quotations, but rather as elements that allow him to access the construction of his own language, almost an alphabet, capable of transcribing a vision of the world through rapid, vibrant, elegant, urgent and intensive writing.

Indeed, the hieroglyphic dimension – which I mentioned earlier – acquires strength in our eyes, so we realise that, thanks to it, we are led to witness, as if looking at a large screen, an experience that’s similar to the one being offered that possesses a form of writing.

Hence, as in the Japanese character, whose meaning is at the same time graphic, visual and syntagmatic, we could also say here that, almost in the style of the great Saul Steinberg, everything is structured according to a flowing pictorial logic and, in some respects, similar to that which presides over the construction of Japanese Ukiyo-e engraving.

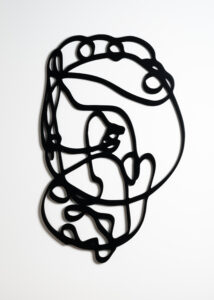

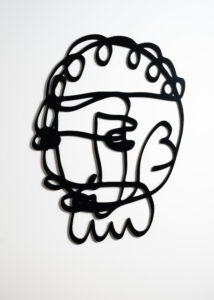

However, in Danilo’s work, these images that evoke an oriental character now acquire a sculptural aspect. The artist chooses to confer three-dimensionality to them through cut-outs made of wood, which he then paints and which he can mount directly on a wall, where each figure reappears as if on a painted panel. Figures that are free in space, which move from drawing and painting into the sculptural dimension, now serve to reactivate the musical sense of the entire work, which I mentioned above. Generating a kind of dance, populating the walls on which his exhibition takes place, they are living figures of this movement that ties the work of Danilo Bucchi to a new sentiment that could be defined orientalist. Everything acquires the aspect of movement, of fluctuation, of the dynamics of signs when they are freed from immediate meaning and consigned only to the variability of its being-sign.

Hieroglyphs leap from the paintings and invade the walls, like graffiti on the streets of our cities. They are almost animated by a poetic life of their own, creatures of dreams and fantasy that dance freely in the spaces and allude to a mobile time, which evokes the liquid modernity that Zygmunt Bauman recounts and in whose regime we all come across a moving reality, never fixed, flowing and marked by the dissolution of the previous image we had of the world as a solid.

So, here we will find the sensitive rhythms of these “portraits of the fluctuating world” that have contributed to the glory of Japanese art since the seventeenth century, whose intense representations of urban life would, two centuries later and indelibly, mark Western art starting with Manet, generating new and unexpected forms of representation that led to the birth of Modernity.

Everything here is mobile, intense, at the same time seismic and sign-based. This suggests an apprehension of life similar to the one Roland Barthes learned in the East and which he later called the empire of signs in order to designate this extreme coincidence of life and language, which he believed differentiated Eastern from Western culture.

Danilo Bucchi’s painting is a cinema: in its presence, we just have to let ourselves be carried away by its intense narration, by the fluidity of its gestures, signs, notes, by the way in which it vibrantly transcribes the new poetic order of our time using its own writing style.

Bernardo Pinto de Almeida

March, 2023

[1] – Perniola, Mario. Enigmas – O Momento Egípcio na Sociedade e na Arte. Bertrand, Lisboa, 1994, p. 127. (Transl. by Chiara Mancini)